Select Page

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, in the Palaeolithic era, Stone Age humans had the most basic food distribution systems (FDS): they hunted wild animals for meat; scoured the forests for fruit, roots, and nuts; and then carried them back to their caves for the family to consume. This may have seemed simple enough for those hunter-gatherers, but if they failed to find food, the family starved.

In modern times, FDS have become more complex. “Ideal” systems must align the requirements of consumers, society, government, and commerce to ensure that they can deliver secure, safe, tasty, affordable food for all members of society in an efficient, environmentally responsible manner (e.g., with minimal waste and low carbon impact) on demand from normal weekdays to peak occasions (e.g., festivals such as Chinese New Year) and deliver long-term financial returns to commercial participants. Notwithstanding famines, climate vicissitudes, and unforeseen food production exigencies (e.g., African swine fever and its impact on Asian meat supplies), local and global FDS continue to show considerable resilience. Resilience, as the capacity to react quickly to difficulties, and adaptability in responding to and even anticipating the continually changing requirements of both consumers and society for food are quintessential requirements of modern FDS.

The evolutionary paths of FDS are driven by global economic growth. Small-scale rural farming societies exhibit relatively high levels of food self-sufficiency but, with the commercialization of agriculture, specialization of function increases and food bartering morphs into formal trade. Invariably, economic growth accelerates the process of urbanization, which has a profound impact on FDS development. As the global population increases from 7.8 billion (2020) to close to 10 billion, the importance of mega cities will increase. By 2050, 600 cities (some with the same population size as medium-sized countries) will each have 20–40 million consumers. Many of these will be in Asia and will place daily inexorable pressure on food distributors. FDS must provide just-in-time supplies of food to meet the needs and wants of consumers of every age and income range. Traditional markets will disappear if they fail to respond to changing consumer requirements.

In Asia, the grocery supermarket sector will see continued strong growth in emerging economies but, in time, will be superseded by newer routes to the consumer. The direct delivery-to-home models of distribution which are growing so quickly in PR China are cases in point, illustrated by the meteoric rise of Tmall (Alibaba) and JD.com (partly owned by Tencent). The challenge for FDS entrepreneurs is to be willing and able to embrace disruptive technology as its potential becomes self-evident.

As countries advance economically, businesses within the food chain tend to become fewer and larger, and supply chains exhibit greater degrees of integration. Fresh food provides examples: livestock and vegetable producers grow in size and seek relationships with major customers (supermarkets, restaurant chains, meat processors) who are closely connected to urban consumers. This can present challenges for small-scale producers, who may elect to focus on very local markets or nearby towns where they can establish a differentiated brand as “traditional, local farmers” and sell their produce through revamped farmers’ markets.

Historically, as international trade in food expanded, urban-based consumers tended to lose contact with (and interest in) where their food came from other than “faceless” supermarkets or local shops. However, occasional food safety scandals (e.g., the 2008 melamine tragedy in China) and food chain integrity debacles (e.g., in Europe when horse meat was sold as beef) eroded trust in food industry participants (particularly in major food companies or so-called Big Food). As a result, consumers worldwide are increasingly interested in who produces their food and how, where the ingredients come from, how it reaches them, and its impacts on the environment (e.g., carbon footprint), farmers and other food businesses, and the local economy. Modern FDS must now provide much more transparent, traceable information on the channels along which food moves to final consumers. This underlines one critical requirement of FDS: they must engender trust among consumers and all other food system participants.

It is easy to take the functioning of modern FDS for granted. Under normal circumstances and in most countries, food is readily available. Purchasing it can be a problem for those with insufficient incomes, but most households can at least get by, until there is a problem. Then, everybody, from consumers, the media, and the food industry itself to government, becomes hugely interested. Our relationship with food is visceral: without it, we starve. One of the most important regulatory functions of government is to ensure that citizens are adequately and safely fed. In modern FDS, participants understand the roles that both the private and public sectors must play in ensuring that food is safe and that “what it says on the label is what is actually inside the package.” Food fraud is a considerable problem worldwide, and fraud in concert with unsafe food can be a huge destroyer of trust in any FDS.

Public and private agencies have a joint responsibility to ensure that FDS have the highest integrity. Problems in one country’s food system can be dangerous for public health and destroy consumer trust in brands that have been built up over many years. That has led the food industry to increase initiatives to improve overall standards within FDS. The use of hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) analysis was embraced by leading food industry firms in the 1960s, and now blockchain technology is increasingly seen as an important global “trust builder.” For example, a mobile app using the Farmer Connect traceability platform powered by IBM Blockchain was launched in January 2020, allowing consumers to trace coffee beans to the point of harvest by scanning a Quick Responde Code on the cup or package using an interactive map.

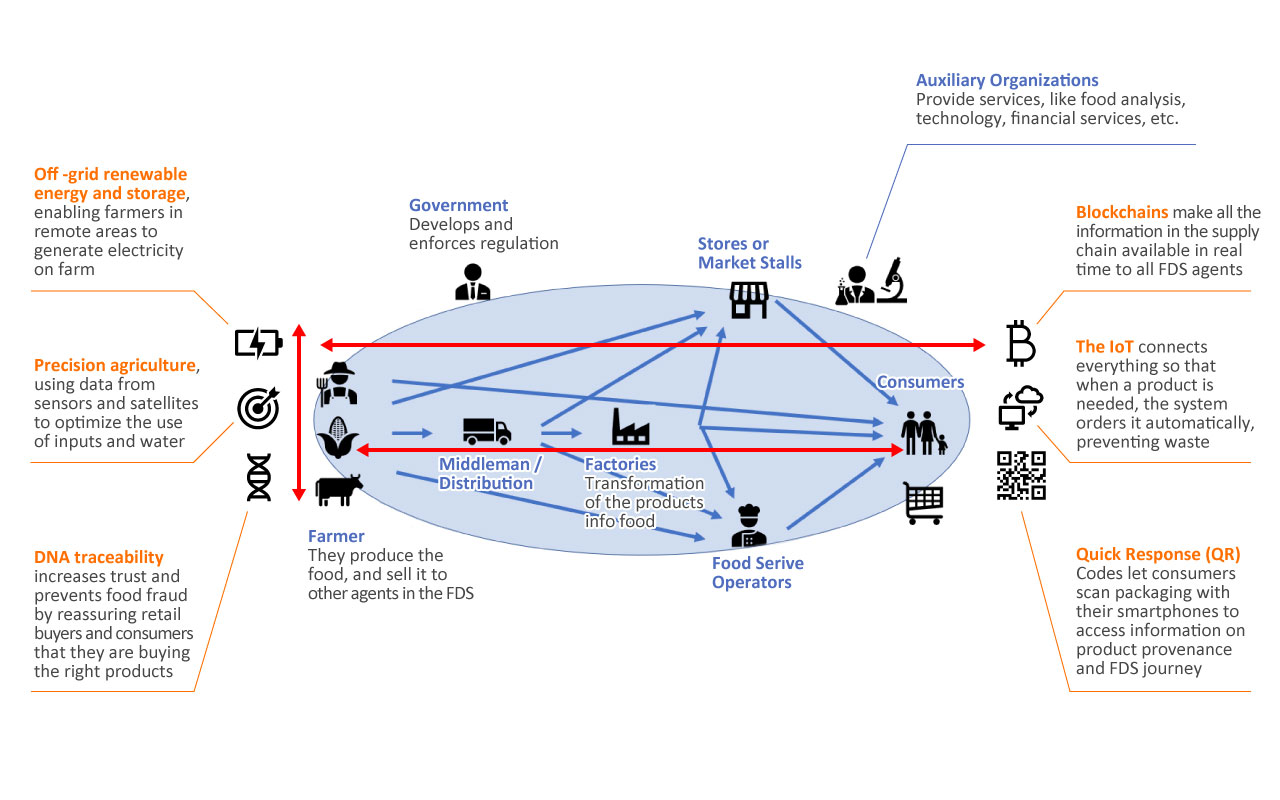

Modern consumers around the world are technologically savvy and increasingly demanding of food products and services. This requires a consumer-centric FDS that can change as customers change, while simultaneously ensuring that FDS activities respond to evolving social concerns (carbon emissions, food waste, recyclable packaging, treatment of farmers and animals, etc.). In a few short decades, IT advances have transformed communication among FDS members, including consumers. Agents in FDS are connected vertically and horizontally through IT, reinforcing the notion that FDS are dynamic networks rather than linear chains (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scheme of modern FDS with examples of technological linkages to improve product visibility and traceability and increase FDS productivity.Adapted with permission from Hughes D. and Flavian M., 2019.

21st century technology is transforming the efficiency of modern FDS and its applicability is as relevant in emerging markets as it is in developed ones. It is a shocking fact that one-third of the world’s food supply is wasted before being consumed. Particularly in emerging markets, inadequate food distribution infrastructure is responsible for much of the waste (e.g., poor on-farm and wholesale storage and supply chain transport). This must be addressed. However, a combination of improved infrastructure facilities, better management, and the use of technology to provide real-time information on product availability and quality provides an opportunity to transform productivity in modern FDS across the globe.

One thing is certain: the rate of change in the global food industry will accelerate, requiring concomitant change in the structure and operations of FDS. Consumers want to buy an ever-increasing range of food whenever and wherever they wish. Omni-channel food distribution is emerging across the globe, not least in Asia. Consumers can buy food online or in traditional stores and super/hypermarkets, procure food directly from producers via the Internet, eat away from home or have restaurant meals delivered to their doors via motorcycles and robots, purchase ready-made meals that can be microwaved and on the family table in a flash, buy meal kits where fresh food ingredients are prepared elsewhere but cooked at home, or eat on-the-go meals or snacks from vending machines. These methods offer products meeting very specific dietary needs (e.g., allergen-free food). The fast-growing range of options will bring greater complexity to modern FDS along with expanding opportunities for individuals and businesses involved in them.

Dr. David Hughes is the expert of the APO e-learning course on Modern Food Distribution Systems. Course description is available here.

Dr. David Hughes is Emeritus Professor of Food Marketing at Imperial College London, UK. He is a frequent speaker at international agricultural and food events and works closely with agribusiness and food industry companies and organizations in Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Dr. David Hughes is Emeritus Professor of Food Marketing at Imperial College London, UK. He is a frequent speaker at international agricultural and food events and works closely with agribusiness and food industry companies and organizations in Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.