Select Page

Labor shortages are affecting many developed countries, including those in the APO region, making automation a potential solution to boost productivity. Through literature review, this article looks at how automation is changing and examines its effects on jobs and productivity, as well as the balance between using robots and relying on migrant labor to address workforce gaps.

The robotics landscape in APO members

Robotics is divided into two main categories: industrial robots and service robots (Schneider et al., 2018). Industrial robots are heavily utilized in sectors like automotive, electronics, and machinery. Within this, robots are further classified as traditional and collaborative, with collaborative robots currently representing only 10% of industrial robots globally. Meanwhile, service robots do not produce anything but perform useful tasks for humans or equipment excluding industrial automation applications, such as medical services, professional cleaning, and transportation and logistics (International Federation of Robotics, 2024).

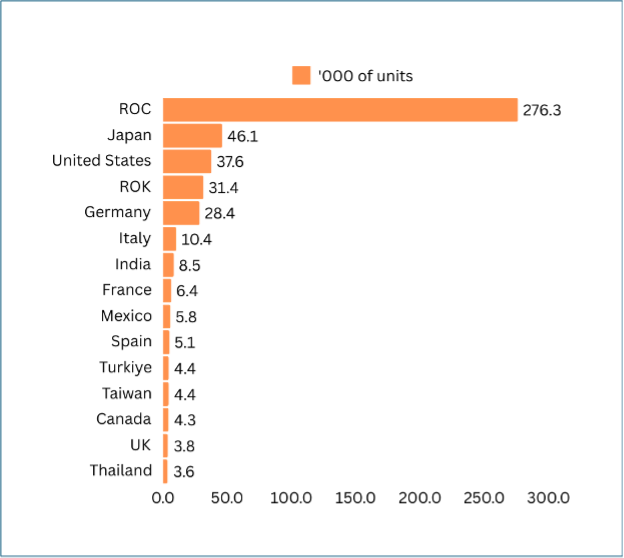

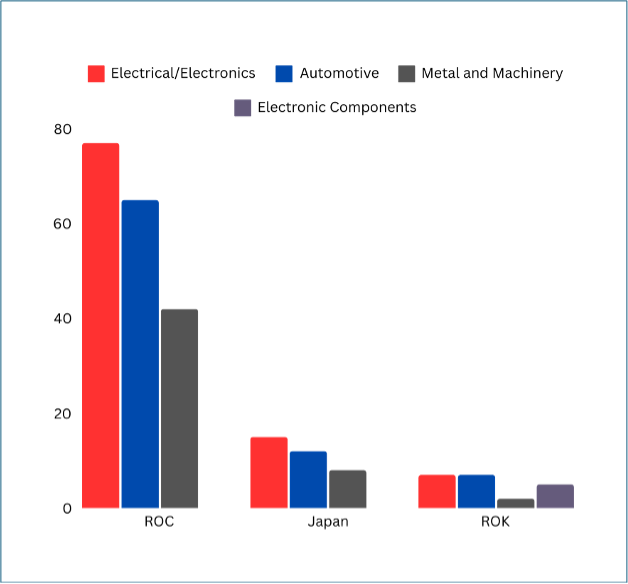

Among APO members, the ROC, Japan, and the ROK are listed among the five largest markets for annual installations of industrial robots, of which 51% of installations are in the ROC (International Federation of Robotics, 2024). Figure 1 shows the annual installation of industrial robots in 2023. In terms of the customer industry of robotics installations, electrical/electronics had the highest number of annual installations in those three countries, with the ROC reaching 77,000 units in 2023, followed by automotive and metal and machinery (Figure 2). In the ROK, electric components/devices are also leading the industry with average installation during 2021–23 of 4,091 units per year. The ROC, Japan, and the ROK are also listed among the top 10 service robot suppliers.

Figure 1. Annual installations of industrial robots (2023)

Source: Author, reproduced from the International Federation of Robotics (2024).

Figure 2. Annual robot installation by customer industry (2023)

Source: Author, reproduced from the International Federation of Robotics (2024)

Japan, often dubbed the “Land of the Rising Robots,” has pioneered robotics across multiple industries. Japan’s most productive sectors—automotive and electronics—rely significantly on automation, which has led to substantial productivity gains. As Japan’s labor force declines, SMEs in particular struggle to attract and retain workers, making automation an increasingly attractive option (Hamaguchi and Kondo, 2017). This demographic trend is not unique to Japan, but Japan is experiencing it more acutely than other developed economies.

Automation and employment

The rising demand for automation is driven largely by severe labor shortages. An aging population is also driving demand for robots outside traditional industries, extending into schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and even public spaces like train stations. Japan, for example, was experiencing service quality declines due to labor shortages and relied on automation to help maintain or even improve service standards in sectors such as healthcare, education, and retail.

New technologies can displace or augment tasks performed by workers, impacting the distribution of tasks between humans and machines and affecting productivity (Acemoglu & Restrepo 2019a, 2019b). Technology can automate tasks, replacing labor with machines (e.g., office software or robots for welding). It can also create new-labor intensive tasks, like drone operators or AI trainers. In terms of productivity, substituting machines for labor can reduce production costs and increase labor demand in nonautomated tasks. Simulations by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest that while increased automation may lead to declining labor shares and rising inequality globally, Japan could experience unique benefits due to its shrinking labor force (Morikawa, 2018). Automation in Japan could potentially boost wages and economic growth, allowing the country to offset the effects of a reduced labor pool.

Various studies show a positive correlation between automation and jobs. A study on the impact of technology in Asian countries found that productivity gains through technology led to a net increase of 33 million jobs per annum between 2005 and 2015 (ADB, 2018). If the increase in production results in wage increases or increased employment overall, increased demand spills over into other sectors of the economy, creating a virtuous circle of increased productivity, increased demand, and increased wages and spending power, leading to increased demand for other products and sectors (Zierahn et al., 2016).

Kawaguchi et al. (2024) studied robot prices to estimate the causal effect of robot penetration on labor demand, using case studies in Japan from 1978 to 2017. The study revealed that a 1% decrease in robot prices led to a 0.43% increase in employment. This indicates that robots facilitate work-sharing and time-saving technological advancements, boosting hourly productivity among employed workers. A significant presence of robots contributed to higher employment levels, suggesting that the scale effect from robot adoption outweighed the substitution effect (Adachi et al.,2022). Furthermore, the findings consistently demonstrated positive impacts of robot adoption on employment, working hours, and wages across various demographic groups, with the exception of older workers.

In particular, manufacturing often generates strong spillover effects within the sector and in complementary sectors (Cowen, 2016). However, this does not seem to apply to Japan, where the situation is quite different. Japanese manufacturers have successfully adopted robotics to reduce production costs, lower output prices, and increase output. However, across-industry, within-region spillovers are limited. The positive employment effect is largely confined to the manufacturing sector and does not extend to the non-manufacturing sector or to individuals who are unemployed and rely on working family members (Kawaguchi et al., 2024).

Automation and migrant labor

The relationship between automation and migrant labor is still under discussion among academics and policymakers to determine whether it is complementary or substitutive, especially as there is not much research on the response and conditions of migrants in the face of automation. To meet demographic challenges, developed countries relied on automation as a new solution path over immigration. However, a country must address social risks, such as workforce polarization, to ensure that automation benefits all sectors of society.

Zhou et al. (2024) reported that cities with greater exposure to industrial robots were more likely to attract migrant workers to settle. This is primarily driven by the shift away from routine-intensive jobs, the reintroduction of high-skilled, machine-complementing roles, and an indirect rise in service-based jobs across skill levels. Beyond economic incentives as the main impact pathway, analyses of these mechanisms reveal that the resulting labor market adjustments also promote the social integration of migrant workers, serving as a secondary influence on their willingness to settle.

In 2022, Mann and Pozzoli performed an experiment on quasi-random placement of immigrants across local labor markets and firm-level robot data in Denmark. The study found that immigration and automation act as substitutes, with a higher proportion of migrant workers in a local area leading firms to adopt fewer robots. Since migrants are often less skilled than native workers and tend to occupy routine-intensive roles, the findings suggest that low-skilled workers and robots serve as alternative solutions for addressing labor shortages. This aligns with Kawaguchi et al.’s (2024) findings, which indicated that a decline in the relative cost of robots influences the demand for both robots and labor through substitution and scale effects.

Several variables influence countries’ adoption of robotics as a productivity solution in addition to migrant labor. The first is robot price and durability. In the case of Japan, the manufacturing sector has successfully utilized robotics to reduce production costs, lower output prices, and expand capacity. The second variable is range of tasks. Industrial robots handle a variety of tasks, although some roles remain exclusive to human workers. Robotic task exposure is the third variable. Japan’s industrial output is highly responsive to robot prices, making cost-effective automation a priority (Schneider et al., 2018). Fourth, robotics are preferred in the context of cultural homogeneity in Japan (Koudela, 2019).

Conclusion and recommendations for further studies

Labor shortages and aging populations in developed countries, including APO members, have driven increased reliance on automation as a solution for sustaining productivity and economic growth. Automation enhances productivity by substituting workers on repetitive tasks with machines, enabling workers to focus on higher-value activities. While automation has positively impacted employment, particularly in manufacturing, its benefits remain uneven across sectors and demographic groups.

The interplay between automation and migrant labor remains complex, with mixed findings on whether it is complementary or substitutive. Automation has encouraged high-skilled job creation and social integration of migrants in some regions, while in others, it has substituted low-skilled migrant labor in routine-intensive tasks. These dynamics underline the importance of targeted workforce strategies to ensure that automation benefits all sectors of society equitably.

Below are recommendation for further studies:

Addressing these areas will enable policymakers and businesses, particularly in developed countries, to better harness the potential of automation balanced with the utilization of existing migrant labor pools.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019a). Artificial intelligence, automation, and work. In: The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda. University of Chicago Press,197–236.

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019b). Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 33, 3–30.

Adachi, Daisuke, Daiji Kawaguchi, and Yukiko Saito, 2024. Robots and employment: Evidence from Japan, 1978-2017. Journal of Labor Economics , Volume 42, Issue 2 (2024), 591-634. https:/ /www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/723205

Asian Development Bank. (2018). Asian Development Outlook 2018.

Cowen, T. (2016). Economic Development in an ‘Average is Over’ World. George Martin University.

Hamaguchi, N., & Kondo, K. (2017). Regional Employment and Artificial Intelligence. RIETI Discussion Paper 17-J-023, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, Tokyo.

International Federation of Robotics. (2024). World Robotics 2024.

Kawaguchi, D., et al. (2024). Factory Automation, Labor Demand, and Local Labor Market. IZA DP No. 16885. IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Discussion Paper Series.

Koudela, P. (2019). Robots Instead of Immigrants: The Positive Feedback of Japanese Migration Policy on Social Isolation and Communication Problems. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 19(1): 89–102.

Mann, K., & Pozzoli, D. (2022). Automation and Low-Skill Labor. Discussion Paper Series: IZA DP No. 15791.

Morikawa, M. (2018). Labor Shortage Beginning to Erode the Quality of Services: Hidden Inflation. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, Tokyo.

Schneider, T., et al. (2018). Land of the rising robots. F&D Finance and Development Magazine. IMF.

World Bank. (2024). Jobs and Technology. World Bank East Asia and Pacific Economic Update (October 2024). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zhou, J., et al. (2024). Are robots crowding out migrant workers? Evidence from urban China. Habitat International 152, October, 103154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2024.103154.

Zierahn, U., et al. (2016). Racing with or against the Machine? Evidence from Europe. Discussion Paper No. 16-053, ZEW Centre for European Economic Research.

Santi Setiawati is a Program Officer in the Multicountry Division 2 at the Asian Productivity Organization (APO). She holds a Master of Public Policy from the Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP), The University of Tokyo, Japan. Her professional interests include capacity building, training, and research.