Select Page

Within the last 10 years, the share of renewables in electricity production tripled. Renewable energy (RE) is the second biggest energy source behind lignite (25.8%) and now delivers 23.9% of Germany’s total energy production. Currently, Germany has a total installed RE capacity of 84 GW out of total installed electrical capacity of 160 GW. The total investment in RE in 2013 was €16.3 billion, and more than 370,000 people were employed in this sector.

Today, the German government is working on the so-called Energy Transition (Energiewende) as the biggest national infrastructure project. The main political objectives of the Energy Transition are:

Core strategic targets

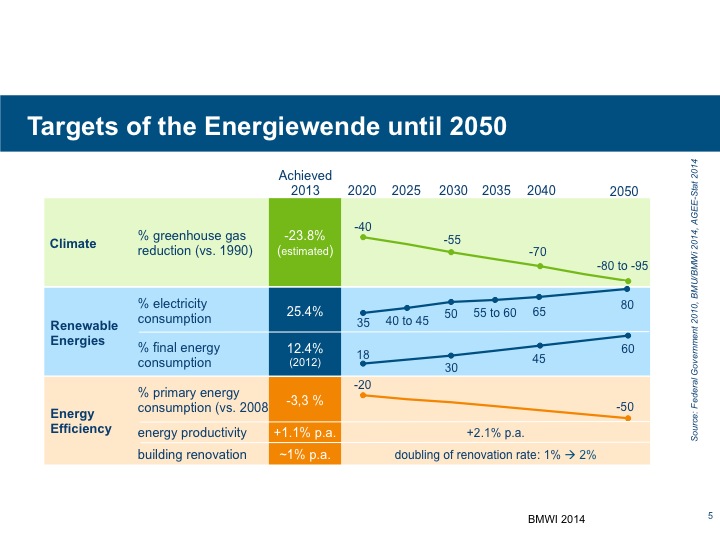

Based on the political objectives, the German government defined two core strategy targets as pillars of the Energy Transition (Figure 1). The first is to increase the share of RE in the overall energy mix. The energy supply will switch to a portfolio dominated by RE like wind, solar, geothermal, biomass and waste, and hydropower. RE will deliver 35% of electricity consumed in 2020 and 80% in 2050. The second is to increase energy efficiency (EE) and reduce energy consumption (Figure 1). The target is a reduction in primary energy consumption of 20% in 2020 and of 50% in 2050 vs. 2008. Energy productivity should increase to +2.1% annually. The results so far are remarkable, and Germany is on track to reach its long-term targets.

Figure 1. Targets of the Energiewende (Energy Transition) until 2050. Drawn by the author based on data from the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWi) and Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU).

Renewable Energy Act

The Renewable Energy Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz) supports the promotion and deployment of RE. It was the major success factor over the past 14 years because its enforcement has enabled RE use to grow at a rapid pace. The core principles of the Renewable Energy Act are: 1) Renewables have guaranteed grid access and priority transmission and distribution. Network operators are required to feed this electricity preferentially into the grid. All have the right to become a utility and to feed electricity into the grid. 2) Every kWH generated from RE facilities receives a fixed feed-in-tariff (FiT) for a specified period, usually at a premium price reflecting the higher costs of RE compared with fossil fuels. 3) There is no charge to public purse. The FiT is not a subsidy and not dependent on the tax budget. The additional cost or difference between the FiT paid out and wholesale stock exchange price is shared among all energy consumers.

These three principles lead to investment security, which builds the foundation of sustainable growth in RE. The positive experience in Germany shows that a FiT in combination with guaranteed grid access is the most successful model for the deployment of RE. This simple, straightforward model has lowered prices to the extent that solar systems in Germany are the least expensive worldwide.

The idea is that anyone generating renewable energy can sell the energy (kWH) produced for a 20-year fixed period. Tariffs are set to ensure a modest Return On Investment (ROI). The FiT supports each technology in relation to its market position and technological maturity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Feed-in tariffs provide investment certainty and drive costs down: simplified generalization of feed-in tariff with 20-year duration. Reprinted, with permission, from Energy Transition—The German Energiewende. Heinrich Boell Stuftung; www.energytransition.de.

Once the system is connected to the grid, the FiT is fixed for 20 years. Each year the rate drops only for newly installed systems. The idea behind the annual reduction of the FiT is to force price cuts, which are possible in accordance with the growth in market size and the corresponding learning curve. The overall target is to bring RE technology to a pricing level competitive with that of traditional energy sources.

Based on the success of the Renewable Energy Act and constant cost reductions for RE systems, the German government has started a transition from FiT toward a more market-based model. The Renewable Energy Act is the most successful political tool, which has enabled the deployment of RE sources and made them cost-competitive with traditional energy sources.

Feed-in-Tariff and System Prices

A feed-in-tariff (FiT) ensures a modest return on investment for the investor and encourages market growth. Growing markets and the increase in production capacity and output lead to cost savings due to scaling effects and learning curves. The annual decrease in the FiT makes sure that the cost-savings result in lower market prices for renewable energy systems. The most impressive example is the development of small photovoltaic systems (up to 30 kWp) as the following table shows:

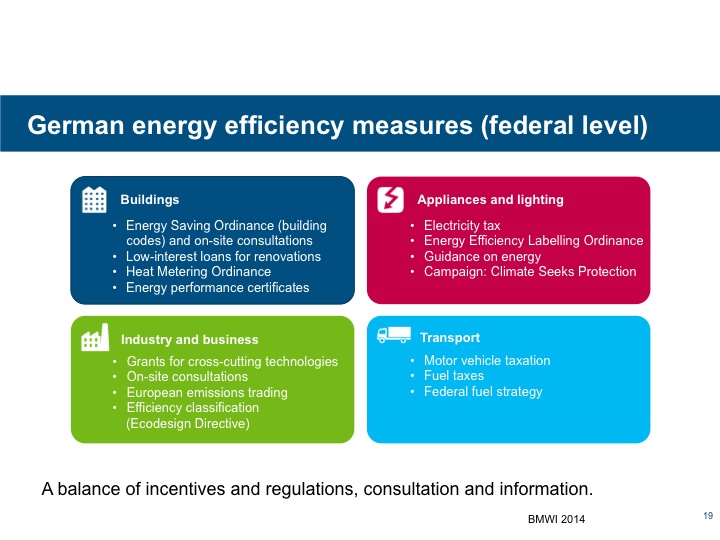

EE

EE, called “the world’s most important fuel” by the International Energy Agency, is the second important pillar of the Energy Transition. The overall approach to EE is a balance of: 1) legal requirements such as energy saving ordinances, building codes, electricity tax, and EE labeling ordinances; 2)support mechanisms such as market incentive programs, low-interest loans for renovations; and grants for cross-cutting technologies; and 3) information tools such as power checks for low-income households, heating reviews, energy saving accounts, and various campaigns to raise awareness. EE measures are applied to multiple sectors, including transport, industry and business, buildings, and appliances and lighting.

EE measures are applied to multiple sectors, including transport, industry and business, buildings, and appliances and lighting (Figure 3). Two sectors are highlighted in more detail below.

Figure 3. German energy efficiency measures (federal level): a balance of incentives and regulations, consultation, and information. Drawn by the author based on data from the 2nd National Energy Efficiency Action Plan of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2011; BMWi; and BMU.

EE in buildings

Buildings are responsible for about 40% of total energy consumption, and the majority of that (more than 70%) is used for heating purposes. The efficiency targets for buildings are a 20% reduction in heating requirements by 2020 and an 80% reduction in primary energy use by 2050. The most important measures are the Energy Conservation Ordinance (EnEV are building codes), funding for energy-efficient renovations, market incentive programs, and regulations on RE use.

The EnEv specifies that new homes must not consume more than 70 kWh of energy per square meter per year (kWh/m2/pa) for heating and hot water. The EnEV will realize major energy savings compared with the typical energy consumption of about 280 kWh/m2/pa for an unrenovated older house. Germany aims to achieve a climate-neutral building stock by 2050 and wants to double the current rate of EE renovations per year.

EE in appliances and consumer products

The EU directives on energy-related products/eco-design and on energy labeling, which apply directly in Germany and other EU member states, limits the energy consumption of electrical goods. Measures for 40 electrical appliances are already in place. Comparing the energy consumption of typical appliances in 2010 vs. 2000, energy consumption by refrigerators is down by 50%, that of washing machines 30%, and that of dryers 60%.

Is the Energy Transition successful?

Electricity consumption has been distinctly decoupled from economic development. GDP growth grew by 28%, while greenhouse gas emissions declined by 22% in the period 1991–2012 (Figure 4). These results are confirmation that the Energy Transition is successful and Germany is on track to reach its targets.

Figure 4. Germany: growing economy, declining emissions. Change in GDP and greenhouse (GHG) emissions in Germany, 1991–2012. Reprinted, with permission, from Energy Transition—The German Energiewende. Heinrich Boell Stuftung; www.energytransition.de.

Data in this article were taken from BMWI—general information 2013. The figures were reprinted, with permission, from the Federal Government 2010, BMU/BMWi 2014, and www.energytransition.de.

Born in Germany, Uwe Juergen Bauer holds two MBA in Business Administration and Economics. He has been living and working for the last 18 years in the USA, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Since 2004 he has been in senior management positions in the photovoltaic industry. Uwe is the founder and owner of bc vision Pte Ltd., Singapore, a service and marketing company with the focus on global strategy, sales, and business development. The company acts as a business link between European and Asian renewable energy companies and markets.

Born in Germany, Uwe Juergen Bauer holds two MBA in Business Administration and Economics. He has been living and working for the last 18 years in the USA, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Since 2004 he has been in senior management positions in the photovoltaic industry. Uwe is the founder and owner of bc vision Pte Ltd., Singapore, a service and marketing company with the focus on global strategy, sales, and business development. The company acts as a business link between European and Asian renewable energy companies and markets.