Select Page

In their 2017 book The Blue Ocean Shift, Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne devote a chapter to how, in 2009, Malaysia adapted the Blue Ocean Strategy (BOS), designed primarily for the private sector, to develop novel solutions in public service delivery. Called the National Blue Ocean Strategy (NBOS), public service improvement strategies developed under its auspices offer a jump in value at a relatively lower cost.

This article describes why and how Malaysia adapted the BOS and explains the factors that made its implementation in the public sector successful.

Rationale for the NBOS

Before the NBOS, public services were delivered in silos with little collaboration among related agencies. Take crime control. Crime control requires a multiagency approach, from schools to community policing, and from law enforcement to legal adjudication. Given the silo mindset, there was little sharing of resources among departments in solving common problems.

At that time too, Malaysia faced problems of fiscal restraint amid an ever-burgeoning population and the onset of a global recession. Citizens clamored for better, quicker, more affordable public services as they grew weary of the government’s inability to deliver public services efficiently.

The BOS offered a platform to deliver huge benefits to the public at lower costs to the government. By breaking down silos and encouraging interagency collaboration, the BOS sought to reconstruct the conventional boundaries that exist across public and private organizations in service delivery. It also sought to reduce the costs of service delivery by pooling resources among related agencies and deploying those resources to where they were required the most and where the impact of their utilization was the highest.

Over the last two decades of implementation, the NBOS has produced 118 BOS projects in 80 agencies. Those projects improved the delivery of public services and all had to meet the following criteria:

One such BOS project was the urban transformation centers. Twenty centers were established in abandoned buildings that were renovated to house as many as 40 public and private agencies. The public can therefore access all their services under one roof. The centers also operate during extended times beyond the normal office hours.

Implementation approach

Based on the Malaysian experience, the process of identifying a BOS project for improving public services is outlined below.

Step one: Establish an innovation team

The first step is to choose an innovation team in a department. This team will identify problems in service delivery and determine innovative solutions. It is important that key players are involved in the deliberations. Otherwise, ownership of the BOS will not occur and turf wars may stymie any innovative solutions proposed.

The ideal composition of the team should be between 10 and 15 so that it is not too unwieldy as to cause incessant arguments. The number should be enough to reflect the viewpoints of the key players involved in resolving a service delivery issue. The collaborative team should be headed by the agency that is the main stakeholder in resolving the problem.

To create a leap in value, the innovation team has to focus on citizens who are underserved or unserved. For example, if crime control focuses on the major crimes of burglary, armed robbery, rape, and murder, the underserved segment of the population may include those who are vulnerable to street crime, snatch theft, petty theft, and pickpocketing.

The innovation team must command the commitment of the organizational leadership. It would be even better if the political leadership were behind the team’s efforts.

Step two: Know the current state of service delivery

To arrive at a BOS solution, the team should not focus on the operational details of service delivery. Rather, it should see the big picture in terms of the key features of the current service and how greater value could be offered to customers without any increase in cost to the government.

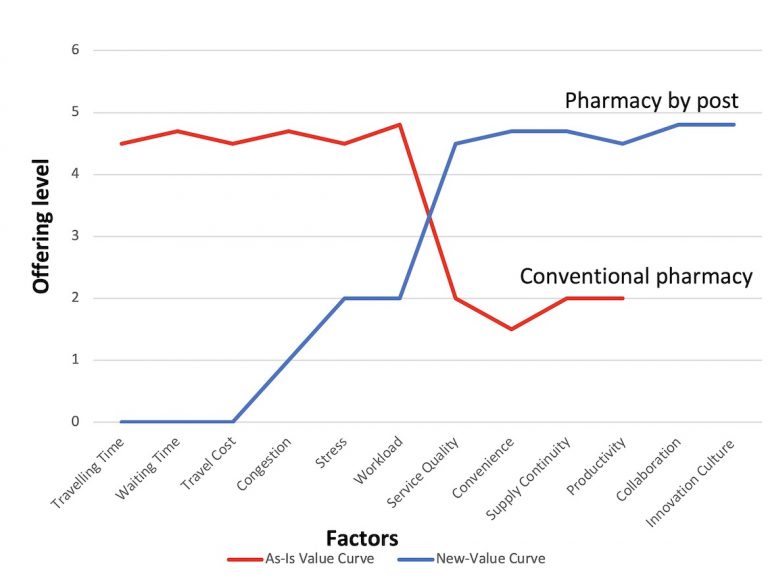

To see the big picture, the team should craft a strategy canvas. The strategy canvas is essentially a graph that highlights the features of the service and the level of offering against each feature. Figure 1 depicts the strategy canvas for the pharmacy services of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. It includes the “as-is” value curve, which captures the current state of play in service delivery, and the “new-value” curve, which represents the BOS. This canvas could also easily represent pharmacy services in other countries.

On the x-axis of the canvas are plotted the features of the service, including activities undertaken in delivering it. The team should identify between five and 12 key factors that currently reflect a particular service provision, especially in terms of time, effort, and investment. The y-axis represents the level of offering, i.e., high (5–6), medium (3–4), and low (1–2) against which each feature of the service is assessed. This assessment must be from the perspectives of the consuming as well as the nonconsuming public. Ideally, they should be surveyed for their opinions. The average scores of their perspectives on the level of offering for each of the factors on the x-axis are then plotted.

The as-is curve that is drawn through the coordinates for the various factors and levels of offering reflects the current state of service delivery. The team can then identify the pain points of the public and the opportunities to improve the service. In the case of pharmacy services, the obvious pain points are waiting time, time and expense in travel, service quality, and stress.

Based on the big picture, the team can then deliberate how the current service could be improved to deliver immense benefit to citizens without an attendant increase in costs. This can be done by reducing the offering levels of the factors that are high and jacking up those with low levels. This raising and reducing should give insights into a BOS. For example, if waiting time is long, then a BOS should reduce waiting time. Similarly, if the stress level (of pharmacists and patients) is high, then the proposed BOS should reduce stress levels.

Step three: Determine a novel strategy

In seeking to offer a novel solution, the team can ask the following questions.

Questions 1 and 2 give value-creating insights, while questions 3 and 4 offer answers to reduce costs. Answers to these questions will help the team to develop the eliminate-reduce-raise-create (ERRC) grid. The grid will then be the basis to draw the new or “to-be” value curve onto the strategy canvas. Table 1 illustrates an ERRC grid developed through asking the four questions below for pharmacy services:

Table 1. ERRC framework for pharmacy services

Figure 1 juxtaposes the as-is and the to-be or new-value curves. The latter points to the new strategy of delivering medicines by post. The greater the divergence between the to-be and as-is value curves, the more novel the solution.

Figure 1. Strategy canvas for pharmacy by post

Reproduced with permission from Xavier J.A., Blue Ocean Solutions: Making the Public Sector More Customer Centric.

Tokyo: Asian Productivity Organization; 2019.

Critical success factors for BOS implementation

Critical success factors for the sustained execution of the BOS include political leadership, implementation machinery, collaborative governance, resources, and mindset change.

Political leadership is crucial

The political leadership should champion the BOS. The bureaucracy will then take the cue that this project is important for improved services. In Malaysia, the then-prime minister initiated the BOS project. However, such reforms run the risk that when the political leadership changes, priorities might change and the reforms might not be championed to the extent that they were before.

Implementation machinery should be installed

Central implementation machinery should be in place for BOS execution. Without such machinery, reforms cannot be applied across the public sector. Tight monitoring and follow-up by a high-level steering committee, chaired preferably by the political leadership, will ensure the sustainability of the reform effort. Additionally, BOS implementation units should be created in ministries to spearhead BOS projects.

Collaborative governance should be forged and silos broken

The BOS requires the pooling of resources across the public sector. It also requires the movement of resources from areas where gains from their use are limited (“coldspots”) to “hotspots” where the value gained from resources expended is much greater.

To undertake such shifts in resources, the breaking of silos and the promotion of collaborative governance are essential. Such collaboration may include strategic partnerships with the private sector and the public.

Sufficient resources should be allocated

For a BOS project to succeed, it should attract sufficient resources so that it can be permanently embedded in the public sector. For example, Malaysia spent USD100 million in 2015 to entrench the BOS in the public sector.

Employees at all levels must be trained in the mechanics of developing blue ocean solutions so that they do not have to rely on top management to initiate ideas.

The BOS requires a mindset change

As with the break-up of physical silos through collaborative governance, mental silos must also be torn down. Employees have to change their mindsets to accept innovative approaches to service delivery. For example, pursuing a new BOS project should be done without the previous mindset of asking for additional resources. Employees must also adapt to new working arrangements. This is especially the case in Malaysia’s urban transformation centers that operate over weekends and late into the night.

Conclusion

The BOS seeks to pursue value innovation in service delivery. To ensure its proper institutionalization in the public sector, political and bureaucratic leadership should champion the project. Adequate resources should be devoted to institutionalizing the reform effort, and employees must be trained in the mechanics of developing blue ocean solutions. Collaborative governance is the buttress of the BOS. This is essential to break up silos to enable the sharing of resources across related ministries that seek to achieve common goals.

Malaysia successfully pursued its NBOS and reaped significant benefits in terms of improved public services. Other countries could similarly profit from implementing the BOS.

Click here for The Blue Ocean Strategy Part 2: Executing the Blue Ocean Strategy.

Professor Datuk Dr. John Antony Xavier is a Visiting Professor at Putra Business School, Malaysia. Prior to moving to academia, he was an Administrative and Diplomatic Officer in the Malaysian public service for 36 years. His current research interests are corporate strategy, competitiveness, and economic development and public policy.

Professor Datuk Dr. John Antony Xavier is a Visiting Professor at Putra Business School, Malaysia. Prior to moving to academia, he was an Administrative and Diplomatic Officer in the Malaysian public service for 36 years. His current research interests are corporate strategy, competitiveness, and economic development and public policy.