Select Page

At the start of the new millennium, as Cambodia’s economy began welcoming the gradual emergence of SMEs, a young entrepreneur spied a largely untapped market space for a snack company. The company she envisioned would produce quality snacks, products that used good ingredients, were manufactured in hygienic conditions, and had proper labels, bar codes, and expiration dates. It was an ambitious vision, and the products were only one part of it.

Keo Mom, now the CEO of LyLy Food Industry, had a dream for her business that went beyond making a stamp on the industry. The other half of her plan was providing badly needed employment opportunities to Cambodia’s farmers and lower-income groups. Her business blueprint involved producing high-quality, nutritious snacks for the Cambodian market and neighboring countries made in a sustainable way, and achieving HACCP and ISO standards for health, safety, and quality.

CEO of LyLy Food Industry Keo Mom.

It was a noble plan with one problem: she didn’t have enough capital. But in Keo Mom’s eyes, that problem was small. “I needed about USD80,000 and only had USD20,000 in hand, so I sold my two flats,” she said pragmatically. “It was a gamble I was willing to take because I believed that I could make it work. There wasn’t any other local rice cracker snack being locally produced at the time.”

A significant development was also taking place in the industry that deepened Keo Mom’s conviction in establishing LyLy. While there were many imported products on the market, producing the crackers locally and customizing them to local tastes using abundantly available raw ingredients was an inviting prospect. More importantly, Keo Mom was keen to engage the local workforce who desperately needed new employment opportunities. Bringing in modern machines would also mean an increase in production levels, and thus profits would naturally soar.

Lyly Food Industry office in Phnom Penh.

LyLy Food Industry began operations in May 2002 with a headcount of 27. Within a few months, it found itself running into a number of brick walls, namely a lack of human resources, poor understanding of how to operate the machines, and an alarming rise in defective products. Very soon, close to 4% of the snacks in each batch were tossed aside for failing to meet quality standards. As productivity began sinking, fewer products reached the market. It didn’t help that consumers didn’t much fancy local products, leading to low sales growth. This meant that staff weren’t given overtime work as they had hoped to beef up their salaries. LyLy was also straining to gain recognition in a marketplace dominated by imports.

Keo Mom knew something had to be done, and fast, to save the flailing business. She had heard from the National Productivity Centre of Cambodia of a demo project run by the Asian Productivity Organization (APO). She promptly applied and a few local and Japanese experts were assigned to conduct gap analysis. The results took her aback.

“I was very surprised when some unexpected issues were revealed, especially ones concerning low hygiene standards. Added to that were challenges with misplaced machine parts, wastage of raw materials due to poor storage systems, and many more. That was when I realized we had a real problem and I believed that the APO demo project could help sort things out.”

After carrying out study visits and evaluation, the experts recommended the implementation of mainly 5S, Six Sigma, kaizen, good manufacturing practices, and food safety management system training. Keo Mom also had specific outcomes in mind after sessions with the experts, “Like high levels of hygiene; increased motivation, productivity, and profits; a quality product; and a recognized brand name. I believed that the APO’s experts would be instrumental in achieving them.”

Expert and staff during training that is taking place on factory floor.

What was immediately apparent when the project was rolled out was staff reluctance. Many hung back as they observed the changes and the participation rate was dismal. “The staff didn’t want to be involved because the project confronted their existing habits and mindsets,” Keo Mom explained. “They didn’t fully understand what we were doing and so they weren’t open to receiving anything new.”

Expert and staff involved in a training activity on kaizen.

Management worked hard at conveying the project’s purpose and potential outcomes to their teams but it initially seemed like they weren’t getting anywhere. Staff turnover spiked, new staff had to be repeatedly trained, and others were reluctant to step up to their responsibilities. “I guess learning to change was a challenge in itself.” Keo Mom strategized by organizing teams, appointing a leader for each, and announcing incentives to encourage optimal performance. It was essential to keep her staff motivated and create a “sense of belonging” to the company.

By the time the project was halfway through, a notable difference was already seen and felt in the workplace. For a start, safety standards improved tremendously. Systems were created for tools, machines, and raw materials and made for a better work environment. Inevitably process efficiency increased and bumped up productivity. Staff morale also rose and more people were taking ownership of their projects. “By the end of the training, the product defect rate stood at only 0.5%. We set a target for decreasing defective goods and those who achieved them were awarded cash incentives. With better know-how, our staff were actually communicating in more meaningful ways with each other and demonstrated a genuine willingness to help out one another. Things turned around and took off from there.”

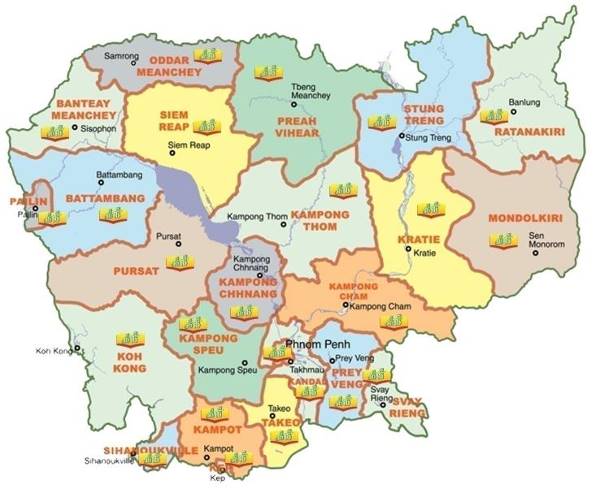

The network distribution of Lyly reaches all of Cambodia.

“The APO training enabled us to introduce 22 new products over the last decade, many of which are sold in the city and the provinces. Plus, our sales hit USD3 million last year.” Lyly’s high-quality offerings rivalled those from overseas, and Lyly Snacks became a household name in Cambodia. “But the greatest benefit to me was the expert consultation and intervention as it really opened my eyes to the real drivers and issues behind productivity, hygiene, food safety, and proper working standards. It also made me more adept at managing crises and identifying opportunities in my business.”

Before and After: Before, trolleys were placed indiscriminately. After, training in 5S taught employees to place trolleys in designated spots between the yellow lines, providing quick access to storage of finished products

Lyly snacks displayed in a supermarket in Cambodia.

In January 2006, LyLy was selected by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) as a model company for its improvement, earning it a higher standard in cleaner production. The company’s marked increases in product quality and better packaging design have since placed it on an equal footing with its two main competitors. To Keo Mom’s pleasure, there were also side benefits, including new trust from customers, staff satisfaction, and a stronger brand reputation.

Keo Mom receiving an award for being the best enterprise in food manufacturing in Cambodia in London, 2015.

LyLy went to sweep an array of awards from 2009 to 2014. The highlights were the First Class in 5S program and the Superior Taste Award in 2013 and 2014, respectively. In March 2015, Keo Mom herself accepted the award for Outstanding Women Enterprise Certificate at the ASEAN Women Enterprise Forum in Vietnam.

Much of LyLy’s success has to do with Keo Mom’s drive and focus but she graciously attributes the starting point to the APO. “It’s so important to receive new knowledge and experiences on management and best practices,” she emphasized. “The APO training has put us on a new path toward extending our market and production process flow. We will soon be Cambodia’s leading snack company in terms of quality, hygiene, and exports.”

The Lyly team having a day of fun after their hard work made the company’s snacks household names in Cambodia.

0 Comments